Throughout my decades working in education and childcare, I’ve developed a deep passion for supporting children with additional needs. Recently, I had the opportunity to attend an interactive workshop on Dyslexia and Mental Wellbeing, which offered fresh insight and renewed understanding on a topic that continues to shape the lives of many children and adults.

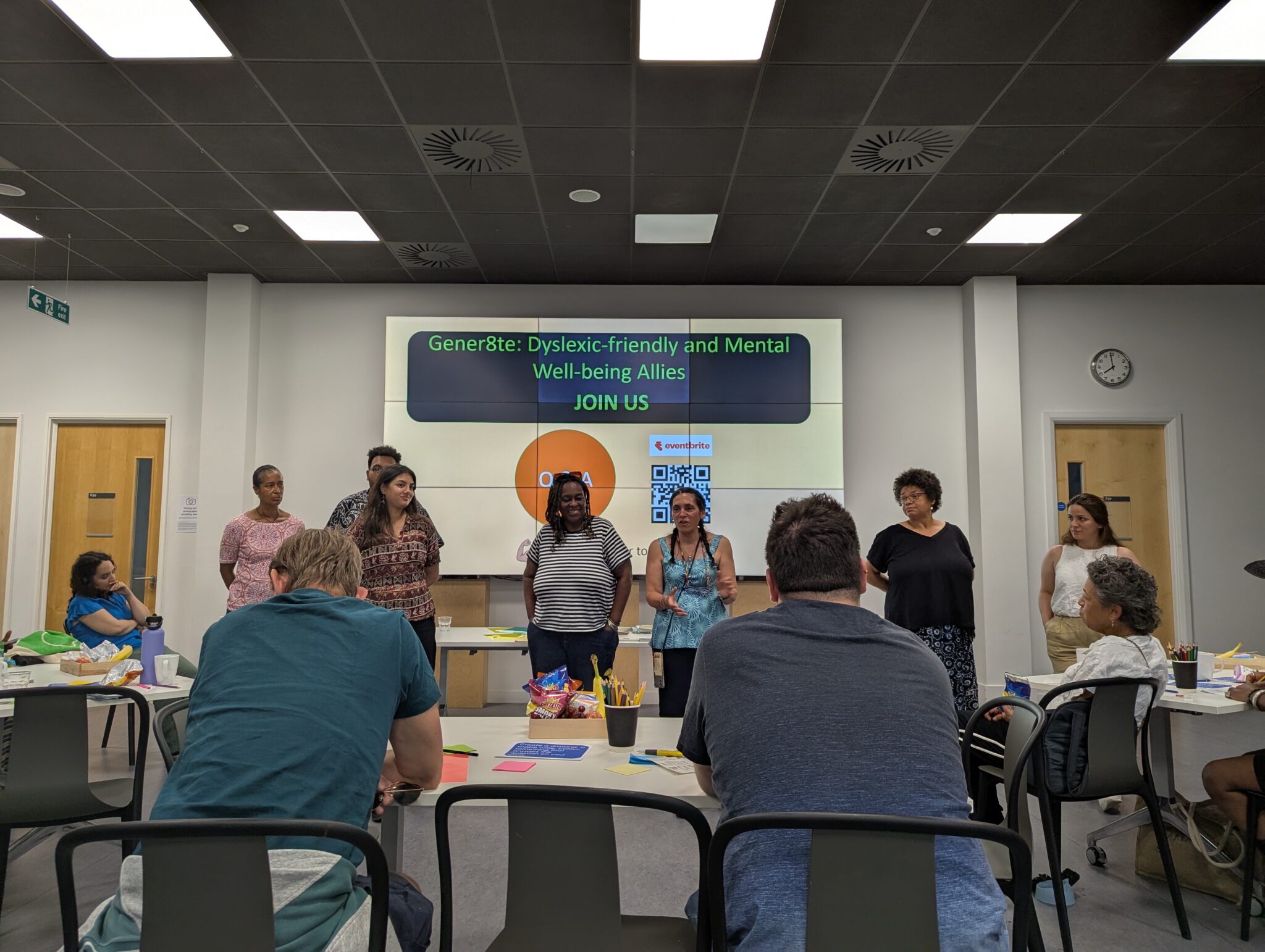

The session was led by Eurydice (Eury) Caldwell, founder of Gener8te (established in 2013), alongside her colleague Noushin Pasgar, a mental wellbeing first aid trainer and DEI (Diversity, Equality and Inclusion) consultant. From the outset, the welcome was warm and genuine.

Eurydice shared her story of being diagnosed with dyslexia and ADHD during university, a late discovery that changed the way she saw herself and her learning journey. She now helps others find confidence, independence, and power in their own stories. Noushin, whose disability was visible from birth, also shared her experiences of undergoing multiple medical treatments as a child and the barriers she’s faced ever since.

The workshop opened with a simple yet thought-provoking activity: participants chose a question printed on colour-coded cards as they arrived, a way of encouraging immediate reflection and open discussion. Throughout the session, Eurydice and Noushin shared personal stories and demonstrated practical tools to support those with dyslexia, including the use of coloured overlays. These overlays help reduce visual stress by softening the contrast between black text and white paper, something that can make reading significantly more accessible.

What struck me most was how different this session felt compared to the ones I’d attended during my time in the early years field. So often, professional training focuses only on defining dyslexia as a learning disability that affects reading and writing, with little attention given to the tools that can actually support people. This workshop felt refreshingly honest and real, full of practical insights from people living the reality every day.

It reminded me of why I do the work I do. Because support shouldn't stop at diagnosis. It should be embedded in the learning environment — in how we design our spaces, adapt our activities, and respond to each child with flexibility and care. That’s the approach I take in my consultancy: not just identifying needs, but equipping staff with the confidence, tools, and strategies to respond in real-time.

It also reminded me how much potential coloured paper and visual supports hold, not just for children, but also for educators. While we may expose children to coloured resources, many adults still aren’t aware of the educational benefits, particularly when it comes to memory, processing, and recall. Visual supports aren’t just helpful for a few – they’re a lifeline for many, and an untapped opportunity for every setting.

This is why visual scaffolding like this is a core principle of Universal Design for Learning (UDL), a framework that emphasises designing environments and materials that benefit all learners — not just those with diagnosed needs. UDL shifts us away from seeing adaptations as ‘special measures’ and towards seeing them as just good practice.

As the discussion deepened, it was impossible to ignore how far we still have to go in terms of inclusion. While slogans like “Inclusion,” “Stronger Together,” and “Embrace All” are widely used in politics and media, people with learning differences still face significant discrimination. Noushin shared that despite being well-qualified, she was repeatedly rejected from jobs after disclosing her dyslexia. Sadly, this remains a shared experience for many.

This really stayed with me because I’ve seen firsthand how much talent, creativity and insight is lost when people aren’t given the right support. And it starts young. That’s why early years provision matters so much: it’s our chance to show children from the very beginning that they belong, that they’re capable, and that their needs will be met with understanding, not judgment.

Another eye-opener was the impact of modern environments, particularly LED lighting, which, while energy-efficient, can trigger visual stress, headaches, and difficulty focusing for dyslexic individuals due to their flicker, glare, and blue light emission.

There’s growing evidence for this. Studies have shown that the flicker rate of LED lights can affect individuals with a flicker fusion threshold under 200Hz - common in dyslexic learners. Research by Wilkins (University of Essex) and the British Dyslexia Association confirms that LED flicker and harsh blue-spectrum lighting can contribute to migraines, poor focus, and visual discomfort.

Despite this, the UK’s Building Regulations and Department for Education lighting guidance make no meaningful reference to neurodiversity. Groups like the Autistic School Makers Project have long advocated for sensory-friendly architecture — yet progress remains slow.

These environmental triggers are often overlooked by institutions like the Ministry of Health and Education, yet they have a daily impact on learning and wellbeing.

It’s a good reminder for practitioners: the environment is the third teacher. And that means we have to be intentional, not just about what we teach, but about what we surround children with. I often work with nurseries to adapt their spaces in small but powerful ways from lighting choices and sensory zones to layout and display.

As the session came to a close, I was moved by the presenters’ encouragement to reconnect with nature, practice mindfulness, and embrace our sensory world, from the textures and sounds around us to frequency-based music that can support calm and balance.

I’m deeply grateful to Eurydice, Noushin, and all the participants for such a transformative learning experience. It reminded me that dyslexic individuals often possess incredible strengths: visual-spatial reasoning, creativity, innovative thinking, and problem-solving skills that challenge conventional frameworks.

From my own experience, I also believe there’s a lack of meaningful adaptation in early years settings for children with specific learning needs. Educators need access to hands-on training like this to move away from the one-size-fits-all curriculum and towards approaches that honour different learning styles. Equally, nursery managers should be equipped with the tools to support their teams, not only for the children’s benefit, but to create truly inclusive environments.

This is exactly the kind of work I do through my consultancy. I offer SEND audits, staff training, curriculum support, and tailored strategies that help settings move from feeling overwhelmed to feeling equipped. Because inclusion isn’t a tick-box - it’s a mindset, a practice, and a daily commitment.

Today, with assistive technology like speech-to-text and word prediction software, many barriers can be removed, giving individuals the confidence and freedom to express their ideas fully.

Let’s take inspiration from role models such as Richard Branson, Lewis Hamilton, and Jamie Oliver, all of whom have learning differences, yet have thrived as entrepreneurs and change-makers. And let’s also create the kind of early years spaces where those future change-makers get their start, not despite their differences, but because we made space for them.

We must stop confining learners to rigid systems. Understanding leads to empathy, and empathy leads to action. Let’s equip people with the right tools, not cast them aside.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is Dyslexia?

Dyslexia is a common, lifelong difference in how the brain processes words and language. It mainly affects skills like reading, writing, and spelling, but does not reflect a person’s intelligence. Many children and adults with dyslexia think and learn in wonderfully creative ways, showing strengths in problem-solving and visual thinking. With the right support, those with dyslexia can achieve and thrive both in and out of the classroom.

What are the 4 types of dyslexia?

There are four main types of dyslexia, each affecting reading and spelling in different ways.

-

Phonological dyslexia makes it tricky to connect letters and sounds, so sounding out words feels tough.

-

Surface dyslexia means recognising words by sight can be a challenge, especially those that don’t sound like they’re spelled.

-

Rapid naming deficit dyslexia slows down how quickly letters or numbers get named, which can affect reading speed.

-

Double deficit dyslexia is a mix of phonological and rapid naming difficulties, which can be a bit harder to manage.

Knowing the type helps us find the right strategies that make learning feel less frustrating and more manageable.

What are the signs of a dyslexic person?

Signs of dyslexia can vary widely, but here are some common indicators to look out for:

-

Difficulty learning and remembering letter names and sounds

-

Confusing similar-looking letters like b/d or p/q

-

Spelling words inconsistently or phonetically, such as spelling the same word different ways

-

Difficulty reading aloud, slow or laboured reading

-

Struggling to sequence events or follow multi-step instructions

-

Poor handwriting or reversing letters

-

Avoiding reading or writing tasks due to frustration

-

Trouble with rhyme or phonological awareness

-

Being bright and articulate but struggling with literacy skills

It’s important to remember that dyslexia shows differently in everyone and often involves a mix of strengths and challenges. Early identification and support can make a big difference.

What does dyslexia do to a person?

Dyslexia affects the way a person processes written and spoken language, making reading, writing, spelling, and sometimes remembering instructions more challenging. It’s not related to intelligence—people with dyslexia often have strong creative and problem-solving skills. Day-to-day, dyslexia can make tasks like reading aloud, organising paperwork, or following complex instructions feel stressful or tiring. Dyslexic individuals may also experience frustration or low confidence due to repeated difficulties, but with the right support, they can thrive and use their unique strengths to succeed

How do you test for dyslexia?

Testing for dyslexia usually involves a full assessment by an educational psychologist or specialist teacher. They look at a mix of skills, not just reading and spelling, to understand the whole picture. This might include:

-

Checking phonological awareness (how well someone hears and works with sounds in language)

-

Testing reading fluency and comprehension

-

Assessing spelling and writing abilities

-

Looking at memory, processing speed, and other learning-related skills

The aim isn’t just to label, but to identify specific strengths and challenges so personalised support can be put in place. It’s reassuring to know there isn’t one single test-diagnosis is about gathering lots of pieces to understand each person’s unique profile and help them thrive.

What is ADHD?

ADHD stands for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. It’s a neurodevelopmental difference that affects both children and adults, making it harder to focus, stay organised, sit still, or manage impulses in daily life. Some people with ADHD are mostly inattentive, some are more hyperactive or impulsive, and others experience a mix of both. ADHD isn’t a sign of low ability – many people with ADHD are creative, energetic, and thrive when supported with the right strategies at home, in school, and in the wider community.

What are the symptoms of ADHD?

ADHD symptoms usually show up as challenges with attention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity. Some common signs include:

-

Finding it hard to focus or get easily distracted

-

Struggling to organise tasks or follow through on instructions

-

Feeling restless or having lots of energy when needing to be calm

-

Fidgeting, talking a lot, or interrupting conversations

-

Acting on impulse without thinking about consequences

-

Difficulty waiting their turn or staying seated

Symptoms can look different from person to person, and some have more trouble with inattention while others show more hyperactive or impulsive behaviours. Recognising these signs early helps get the right support in place so children or adults can manage challenges and shine with their strengths.

How does ADHD affect early childhood development?

ADHD can affect early childhood development in lots of ways because it impacts how well a child can manage attention, impulses, and activity levels. Young children with ADHD might find it tricky to sit still, focus on tasks, or wait their turn, which can make learning and socialising more challenging. They may also experience strong emotions that are harder to regulate and struggle with planning or organising simple daily tasks. These differences can sometimes make friendships and classroom activities more difficult, but with understanding and support, children can learn strategies that help them thrive and build confidence in these early years.

What are the 5 C's of ADHD?

The 5 C’s of ADHD are a helpful framework to support children with ADHD and their families, focusing on building positive, understanding relationships. They are:

-

Self-control: Managing your own emotions calmly, which helps your child learn to do the same.

-

Compassion: Understanding and responding to your child’s unique needs with patience and kindness.

-

Collaboration: Working with teachers, therapists, and others to create a supportive network.

-

Consistency: Keeping clear, predictable rules and following through so children know what to expect.

-

Celebration: Recognising and praising successes, big or small, to build confidence and motivation.

This approach encourages calm, connection, and confidence for both children and caregivers.

What does it mean to be neurodivergent?

Being neurodivergent means that a person’s brain works and processes information in ways that differ from what’s considered typical. Neurodivergent people might experience the world, learn, communicate, or react differently—this includes individuals with conditions such as autism, ADHD, dyslexia, and others. These differences aren’t deficits; they reflect the beautiful variety in how we think and experience life, with every person bringing strengths and perspectives that enrich our settings and communities.

What is the core principle of Universal Design for Learning (UDL)?

The core principle of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is that every learner deserves access to education that meets their individual needs and strengths. UDL is built on offering multiple ways for learners to engage, take in information, and show what they know, so everyone can participate fully. It encourages teachers to anticipate differences and create learning environments that work for all children – not just a select few – by removing barriers and giving genuine choice and flexibility in how learning happens.